The Beating Heart of South American Ambulance Care

https://chat.whatsapp.com/AmbulanceTodayDirect

Published in Ambulance Today, Issue 4, Volume 15, Memoriam Edition, Winter 2018

My fact-finding visit to Quito, capital of Ecuador and home of ISTCRE and CREMYAP took place over Easter, an important time in the South American calendar, since the region is still predominantly and passionately Catholic. My travelling companion was my 15-year-old son, Isaac. Our mission during our week-long visit was to learn more about the workings and mission of ISTCRE, South America’s biggest and best paramedic training organisation, and its off-shoot, CREMYAP, which now leads the way in developing prehospital clinical research across the region. Witnessing ambulance delivery in a country where resources are scarce reminded us that the best people in ambulance are those working in the harshest conditions, facing the most difficult challenges. Along the way we fell in love with a country whose ambulance people possess a spirit as rugged and beautiful as its imposing volcanic Andean landscape.

First Impressions

We landed in the Pichincha province in the Northern Sierra region of Ecuador during the late afternoon on Holy Thursday. We were met by our hosts, Dr Mauricio León, Director of International Relations (and one of the founding team of ISTCRE) and Iván Moya, their International Relations Representative and also a working paramedic.

During the half-hour drive through La Sierra, the Andean highland region of Ecuador, into the centre of Quito we were struck by the sheer beauty of the towering snow-capped volcanic mountain ranges that surrounded us on either side. Despite the fact that the weather was cloudy, rainy and exceptionally grey it was breath-taking. Exhausted, we booked into our hotel and went straight to bed.

Good Friday Daytime: Crowds, Religious Spectacles and Sun-Burn

We awoke on Good Friday to be met with bright Spring sunlight. Our host, Mauricio León, met us after breakfast. We were to spend the day observing Cruz Roja providing medical cover for the second biggest annual public festival in Ecuador, Quito’s Jesús del Gran Poder, or “Jesus of Great Power” procession, which over five decades has grown into one of the largest and most colourful Roman Catholic Holy Week events in Latin America.

Attracting over 300,000 visitors from all around the country and beyond, the procession celebrates the Agony of Christ and consists of around 40,000 participants, most clad in purple silk robes, who proceed from the Basilica in the Old Town to the city’s most impressive cathedral, San Francisco, situated in a vast square, reminiscent of the Vatican.

Many of the participants carry staggeringly heavy crucifixes, others wear barbed-wire which cuts into their naked skin, while still others flagellate themselves as they proceed through the Old Town’s steep and narrow cobbled streets to the echoes of scratchy religious music which blare out of randomly-placed speakers scattered along the route.

Remarkably though, participants pay a fee of between $15-30 US dollars for the privilege of putting themselves through this ordeal which, to put it into context, is a week’s wages for some locals. Those who crowd the pavements to watch the procession treat the day as a jolly Bank Holiday festivity, bringing hampers or buying snacks off the numerous street vendors who jostle for position on every street corner.

ISTCRE’s role involved supplying a number of Command & Control units and other EMS vehicles carefully positioned at key points on the route and providing a couple of hundred fully trained paramedics or volunteer medics who keep an eye on the ever-increasing crowds for those who faint, suffer sun-stroke, sprain an ankle or worse yet, are unfortunate enough to find that today is the day for their long overdue but unexpected cardiac arrest.

As Maurice explained when we arrived at the Basilica where the main unit was stationed: “Our main concentration is on hydration so throughout the route we position booths which gave away free bottles of water.”

In fact, despite the massive crowds the day mainly consisted of treating sprained ankles and dispensing water. Thankfully no serious crimes or medical incidents occurred so the Cruz Roja team could pack up and go home for a rest before preparing for an equally busy evening. Our memory of the day was of the colour, the friendly atmosphere, the sheer exuberance of the crowds and the cheerful efficiency of the Cruz Roja team along the route.

Along the way we fell in love with a country whose ambulance people possess a spirit as rugged and beautiful as its imposing volcanic Andean landscape.

As we followed Maurice and Ivan around the route we were spell-bound by the sights and sounds, particularly some of the colourful, intricate and huge religious icons festooned with flowers which were carried on the shoulders of teams of up to 20 people depicting Christ or the Virgin Mary.

Good Friday Night: Ride-Along from the Inca Station

After a couple of hours rest and a light dinner Ivan picked us up from our hotel and took us to one of Quito’s two main ambulance stations, the Inca base station on Avenue 6th Decembre in the North of the city; based within a socially mixed neighbourhood, it serves some of the poorest and most troubled communities on the fringes of the city, both economically and socially.

Normally housing two ambulances, one of which is a specially-equipped rescue vehicle used particularly when tourists or locals get lost in the surrounding mountain ranges, the Inca station is usually manned by around 10 people per shift, consisting of a mix of qualified paramedics and volunteers—usually ISTCRE paramedic trainees at various stages of their training—it’s modestly scaled with two of those personnel manning a dispatch desk in the corner of the small recreation room while the others either sleep in an adjacent dormitory or drink coffee and watch TV in the same neat and cosy but simply decorated room. But like every ambulance station the world over, all the clinical personnel remain poised to dash to their ambulance the moment a call is taken.

Recognising that Isaac was slightly too young to either go out on-vehicle or stay on his own at the hotel the charming young females in the team quickly took him under their collective wing, inviting him to play cards and making sure that he had a sleeping bag and a pillow ready for when he decided to get his head down for the night.

The wide age range of the team was immediately noticeable, as was the fact that the youngest members were not necessarily the most inexperienced. For example, Gabriel Chapaca, just 20, had qualified as a full paramedic at just 19, while Stalin Landazuri, 44, was a full-time teacher and a psychology counsellor who has been volunteering 1-2 days per week with Cruz Roja for over a decade.

Married to Veronica and with 4 daughters, Stalin is trained to the level of Advanced Search & Rescue skills and happily joked to me that as the sole male in a noisy household of women he looked forward to his night-time voluntary work as a means of getting some “peace and quiet”.

Pleasingly though the gender balance for the shift favoured females, with both dispatchers, Gabriella Franco (24) and Fanny Angelita Inlago (22) and five of the clinicians being women—Vanessa Pallo (21), Denise Vielardo (23), Carolina Jacho (24), Ivonne Quinones (25) and Belen Candela (27).

Between them they ranged from ‘Assistants’, students in the first couple of semesters, up to ‘Advanced’, those such as Belen and Denise who were nearing the end of their course and were due to qualify as registered paramedics.

Leading the team for the night was our friend and escort, Ivan, whose job it was to introduce us to the crew. As Isaac and I were already learning, the two features which distinguished staff, trainees and volunteers across ISTCRE and the wider Cruz Roja family were their boundless good cheer and their amazing enthusiasm for saving lives and improving their life-saving medical skills.

This baby-faced paramedic could, I considered, give Lewis Hamilton a run for his money. Though I doubt that Mr Hamilton would have been capable of getting the ambulance safely to its destination so quickly.

Freddy Baque, a 30-year-old fully- qualified paramedic with the Rescue team explained that he’d begun his relationship with Cruz Roja as a 15-year-old volunteer and was proud to be among the first cohorts of fully-qualified paramedics trained by ISTCRE during its start-up period.

The other senior member for the shift was Edwin Davila, an ISTCRE training professor and also a coordinator with CREMYAP. It struck me as impressive that a course instructor was working on shift with his pupils.

While waiting for the first call of the night Edwin explained the pattern of responses dealt with from the station. As always weekends were busiest but, overall, the surprising thing was how relatively few calls came in.

Six to eight calls on a night shift were considered busy. When I explained to him that UK city-centre crews might handle over 30 calls during a 12 hour shift he was taken aback but explained that since the local population was still not used to having a free ambulance service they rung it only when they considered they had a genuine emergency.

Oh, for such courtesy!

Some of the calls were referrals from the police after, for example, an RTC. Before ISTCRE introduced their service only 4% of patients arrived at hospital by ambulance and these would be wealthier citizens signed up to a private ambulance service. Now 68% of all patients arriving at the ED were transported by Cruz Roja.

The goal, he explained, was that within five years, 90% of all patients would be transported by Cruz Roja. In terms of numbers last year Cruz Roja responded to 5,480 patients, of which only 80% were transported to Quito’s eight public hospitals and 20 clinics after examination.

The prediction for 2019 is that they will respond to 8,000 calls – an increase in call volume of 32%. The big question, he pointed out, is: where will the additional funding come from?

And in terms of those families fortunate enough to subscribe to a private ambulance service what was the average unit cost per transport, I inquired? Around $20 US dollars.

Now, while this may seem cheap to a North American or European person, to put this into context, this is a city where a cab will take you across its entire centre in rush-hour for just $2 US dollars and the average weekly wage for unskilled workers is only about $50.

Last but not least in the team was Daniel Robalino (22) who had qualified as a paramedic the previous year and who was one of two drivers for the night. As I found out later, Daniel was the most skilled ambulance driver I’ve ever spent a shift with. As predicted by Edwin the night was indeed typical.

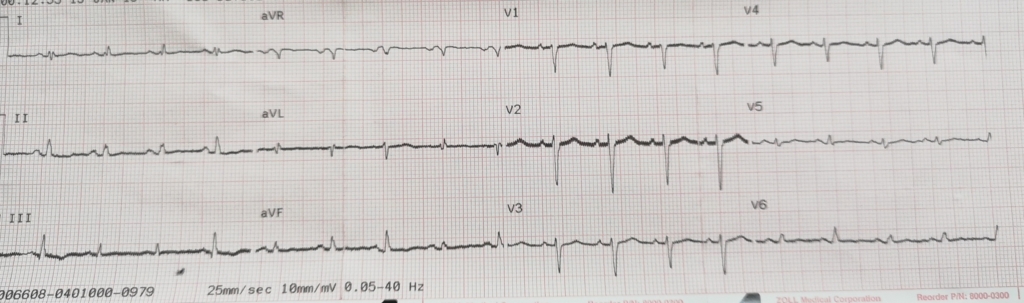

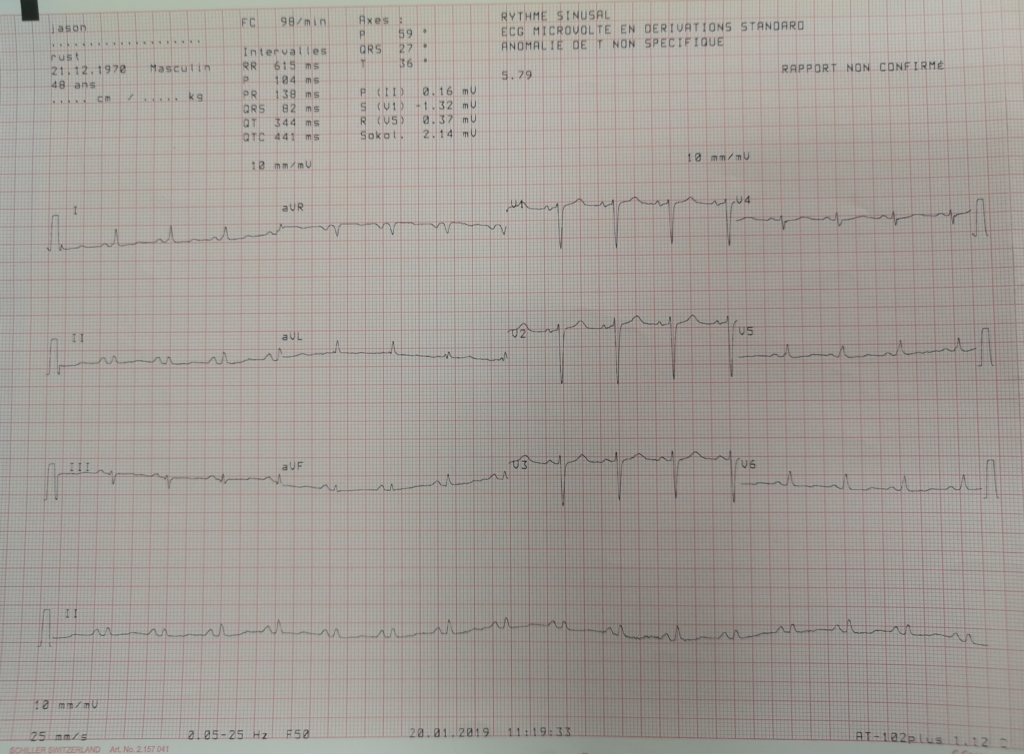

After a couple of hours’ much-needed rest in the dark dormitory on a very comfortable bed we were roused by Gabriella for our first call. Driven by Daniel, with Ivan acting as lead and Vanessa on-board we were called to an elderly female (80) with hypertension and high blood pressure who’d been seen earlier that day by her doctor.

After a careful examination by Ivan, which included testing blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen levels and pupil reaction, it was determined that her condition was caused by a recent change in medication and that she was in no immediate danger. The patient wasn’t transported.

Had she been in Copenhagen, Amsterdam or London she undoubtedly would have been—if only to ensure that the crew were adhering to standard European protocols, which I sometimes feel are designed to avoid blame for the ambulance service, rather than considering the patient’s comfort and best interests.

But as Vanessa explained to me, recognising how scant their actual paramedic and vehicle resources are, ISTCRE-trained paramedics, many of whom have volunteered with Cruz Roja since early adulthood, are taught to both respect the patient’s needs but to also bear in mind that the next call may be more urgent and, if possible, the ambulance and crew should be free to respond.

The next call came in soon after our return to base. By now it was past 01.00 hrs. The only information we had was that the patient was a young male possibly suffering a drug overdose. As we rushed to the vehicle Ivan gave me the option of staying on-station, explaining that the neighbourhood they were heading to, La Volta (‘the Boot’—so called because of its shape) was considered highly dangerous by both ambulance and police.

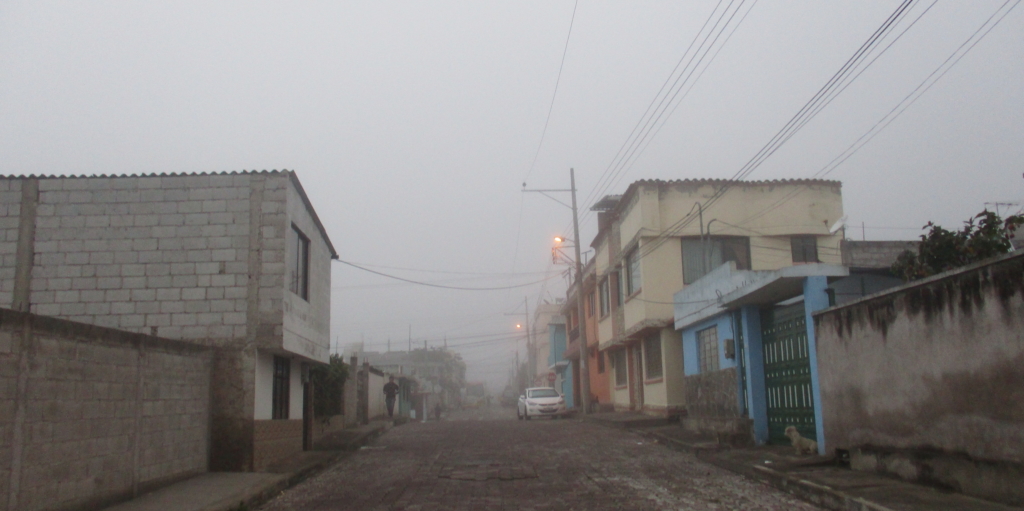

It was not uncommon he said for gangs to either approach the vehicle and intimidate the crew or, worse yet in his opinion, to wait until they were inside the patient’s home treating them and steal vital medical equipment from the vehicle. Explaining that I was content to take responsibility for my own safety, I joined them anyway, and it was during the high-speed 25-minute drive through dense fog along narrow, poorly-paved and cracked roads up steep mountain paths with sharp curves that I realized that Daniel had far from ordinary driving skills.

This baby-faced paramedic could, I considered, give Lewis Hamilton a run for his money. Though I doubt that Mr Hamilton would have been capable of getting the ambulance safely to its destination so quickly. The home of the patient was in one of the poorest neighbourhoods I have ever visited. Consisting of a couple of thousand homes in various states of decay, many boarded-up but still occupied, and most on roads scattered with refuse and with pot-holes the size of buses, they were poorly-lit, if lit at all and there was something else that jarred.

Eventually I realized what it was. “Why are there no shops… no shops at all?” I asked Ivan. He looked at me ruefully and explained: “Sadly, they just don’t work around here. Some have tried to open small grocery stores but they are looted and robbed within hours… often with violence. So as a business model it just doesn’t work.”

When we arrived at the house on a steep narrow road overlooking scrubland, I asked Ivan how Daniel had found it. The area was so dangerous and remote that it literally couldn’t be found via Sat-Nav and the small road didn’t even have a name. “Simple”, he replied. “We develop our own local knowledge because we need to.”

We entered the home to find the concerned family (a mother, a brother, an aunty and a grand-mother) waiting anxiously in the kitchen. With the walls crowded with the Catholic paraphernalia that I had noticed was the norm everywhere in Quito—shops, offices, homes, even street-side kiosks—the first thing that struck me was how immaculately clean and cosy this home was.

After a brief discussion with the brother it was established that the patient, his 20-year-old brother, had spent the evening in an unofficial bar, probably a neighbour’s living room, smoking cannabis and drinking a concoction popular among the local youth – a fruit drink purposefully spiked with methylene.

Why, I asked Daniel, was this a popular drink? His reply made sense: “There aren’t that many bars or liquor stores so young people find their own alternatives. Plus, this drink gets you really high… But it is dangerous, very easy to overdose on!”

When we entered the small, cramped bedroom, two mattresses were on the floor pushed together and the young patient was lying limply on one side with his arms flopping by his side and his eyes closed. Ivan spoke to him gently while encouraging him to do his best to sit up.

After careful questioning to establish the night’s events and a very thorough set of examinations, Vanessa was able to reassure the visibly shaken brother that the patient would be fine. “Keep him awake and give him lots of water” was the simple prescription. The patient wasn’t transported.

“Not necessary”, explained Ivan. “He’s not at any real risk and if he deteriorates, which he won’t, I’ve told his brother to call us back immediately. But it’s Easter weekend and the hospitals are super-busy and to be honest, they can’t offer him anything. He doesn’t need his stomach pumping and the toxins will leave his system if he rehydrates.”

On the way back to base another strange fact struck me. Unlike all other ambulance crews I have observed the world over, the Cruz Roja team behaved differently on arrival. In most cities I’ve visited—from Jerusalem to Las Vegas or from Copenhagen to Quebec—this crew didn’t begin by dragging in stretchers, carry chairs, defibs or whatever else was on-board they could lay their hands on into the patient’s house on arrival.

Ivan explained this to me very simply. “Yes, we’ve got all the basic kit and equipment. Not the most expensive, I know, but it’s all in working order. But the thing is this. Firstly, we know that most of the time we probably won’t be transporting the patient; and, secondly, we really feel that the less dramatic we are when we enter the patient’s home the less stressful it is for them and their family. If we need the carry chair we can always go back out and get it.”

Our final call of the night came in at 4.32 hrs and it was to an even more remote and poor neighbourhood, also in the remote North of the city. During the 15-minute drive I noticed that many of the more populated arterial routes were already awake—if indeed their residents had even been to bed yet. I saw homeless people with their belongings in shopping carts, groups of middle- aged men sat on stoops smoking and drinking and more than one prostitute openly plying her trade by shabby shop fronts, making her pitch to anyone who would make eye-contact.

This time the patient was a 45-year-old man living in a shack on a concrete terrace above the house of a farming family in an oddly rural village-like area, Naxon. It must have been on the very outer Northern border of Quito. The report said the patient had been suffering seizures since the early hours.

When Ivan spoke with his wife it emerged that he had long-term mental health problems and had spent the night kneeling by his bed in prayer and reporting that he was in actual conversation with Jesus Christ who had appeared to him to instruct him to embark on a mission to spread the Good Word. It was after this that the seizures began.

Again Ivan, Daniel and Vanessa embarked on the most careful and sympathetic diagnosis, asking about his prescribed drug regime, and gently asking if there were any issues with either alcohol or any un-prescribed drugs.

The room he and his wife shared was literally a breeze-block shed with a flat roof—the size of a freight container it was undecorated except for rosary beads, a crucifix and a large image of the Virgin Mary. It had bare concrete walls, no carpeting and was crowded with bin-liners overflowing with clothing and knick-knacks. With room for only one rickety bed and a cabinet, this was their home.

Toilet facilities and drinking water were shared with a downstairs neighbour and all cooking and laundry took place on the terrace, regardless of the weather or the time of day. After a long 40 minutes we left and, again, the patient wasn’t transported.

Ivan explained that the priority, which he’d attended to on the spot, was to speak to the patient’s doctor and ensure that later that same day he would be taken to a clinic to meet with a clinical psychologist who could determine the current state of his mental health. Thankfully, he wasn’t suicidal and didn’t represent a risk to anybody around him.

His wife had explained that her husband’s mental health problems had begun 9 months earlier when he lost his labourer’s job and was, despite strenuous efforts, completely unable to find new work. As time passed, due to lack of money, he spent most of his time isolated at home, praying for work. Earlier that day they had found a lift into the centre of Quito to watch the Easter procession. But, as his wife explained, he was bereft that for the first year in many he was forced to watch as an observer since he didn’t have the required $20 needed to participate as a concelebrant.

This she felt, might have been the final trigger to his collapse. He was, I decided, just a very poor and mentally exhausted man who had perhaps lost all hope and self-esteem. Maybe conjuring up visions of his own special and exclusive conversation with his Lord was the only salvation he felt capable of creating.

Despite the kindness shown by Ivan it was impossible to leave without feeling depressed. Sadly, despite their best efforts the Cruz Roja team could offer their patient nothing except compassion and, at least for a short while, a feeling of worth and dignity.

Another Parade, a Panel Discussion and an Unexpected Pop Concert

On Monday morning we went to the Inca Base station, one of ISTCRE’s two main campus sites in the heart of the city. This was the beginning of our official research. Expecting an introductory cup of coffee and a series of scheduled meetings around ambulance training, we were overwhelmed on arrival to see that the entire Institute had prepared an elaborate and impressive parade for us to inspect.

Javier Sotomayor and Mauricio took us around an enormous courtyard where ambulances, rapid response cars, responder motorbikes and entire platoons of staff were stood in orderly ranks so we could greet them and begin learning about their various roles. Everyone was in smart uniforms and smiling and, sometimes in halting English, delighted to explain about their particular role.

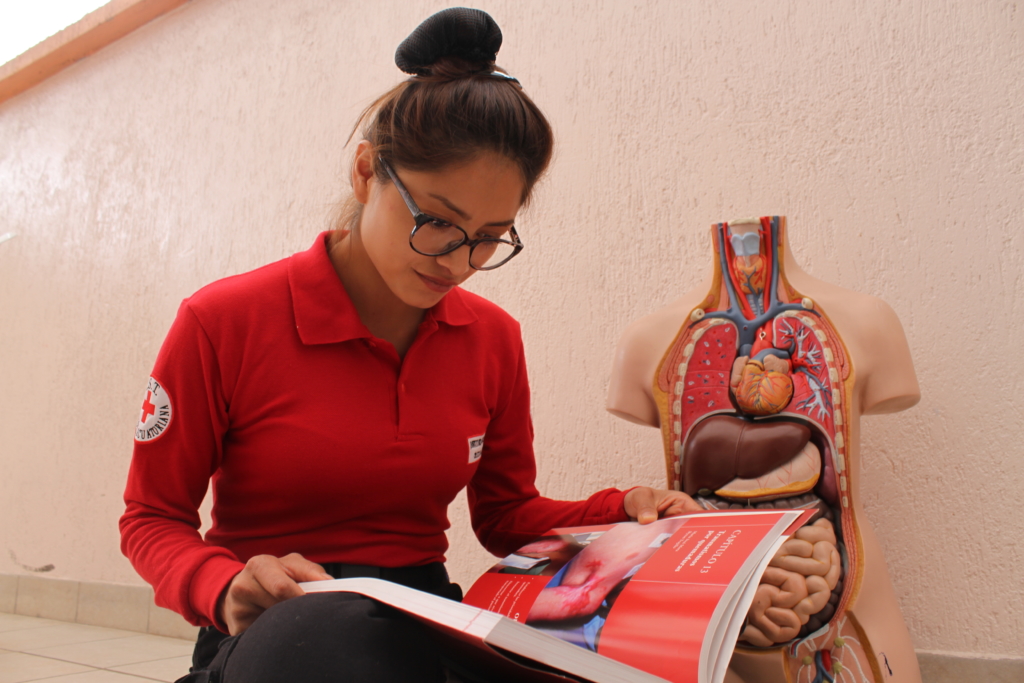

We met teams from their specialist motorcycle responder unit, from their driving school and their specialist rescue team as well as numerous students and instructors. This was followed by a guided tour through their classrooms where we saw students at various stages in their paramedic training engaged in everything from basic first aid, to advanced CPR, to advanced trauma management and even rescue at height, in water, and vehicle extrication.

In every classroom the atmosphere was concentrated and disciplined, yet overwhelmingly enthusiastic with a clear bond of trust and respect between all students and professors.

Next on the agenda was our first contact with CREMYAP – the prehospital research body affiliated to the training organisation which only last year launched Ecuador’s first ever prehospital journal—‘Revista De Investigacion Academica Y Educacion’—an excellent clinical research publication which encompasses both the clinical, psychological and social aspects of national and international ambulance care. One of its excellent first research papers on Burnout among health-care workers is reprinted in English later in this edition.

ISTCRE is a superbly well-organised academic institution—bustling and busy but with teaching staff and students all moving around in a constant blur of happy chatter and camaraderie. Although not notified in advance we found ourselves taken to a main assembly hall with rows of chairs and a stage where I was informed that I was to be a guest panellist on a debate on the future of South American paramedicine comprised of myself and the editorial panel for CREMYAP’s already successful journal.

The hall was thronged with students at all stages of their six-semester degree and the debate was chaired by then Deputy-Rector, but now Rector, of ISTCRE, Dr Victor Daniel Malquin Fueltata. Also among the panel were Dr Jaime Flores Luna, Dr Eric Enriquez Jimenez, Dr Gustavo Cevallos Parades and Dr Wagner Naranjo Salas.

With Mauricio chairing and translating patiently, over 50 minutes we covered a broad and impressive range of issues with me mainly doing my best to offer ad hoc feedback on the current research and thinking on these issues in other parts of the world such as Europe, India, Australasia and Africa.

Topics covered included the latest developments on prehospital pain management (which took in an enthusiastic discussion on the introduction of Penthrox from Australia to the UK), the measurement of standard competencies of EMTs and their global variances, advances in simulation training (which focused mainly on the USA and Denmark), the use of technology in dispatch, which covered the role of IAED (the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch) as a disseminator of best practice protocols globally, and the exceptional achievements of Israel’s MDA (Magen David Adom) ambulance service who have developed possibly the best technology for the control room of any ambulance service in the world—all built in-house!

Other topics covered included mental healthcare for paramedics and remote learning. But the most impressive part of the debate was the fact that the panel encouraged the students not only to ask questions but to express their opinions and ideas frankly and confidently—all of which were listened to and responded to in the most respectful manner.

By late morning I was looking forward to a strong cup of Ecuadorian coffee, a sneaky cigarette break and maybe even a sandwich. But no, not yet. As soon as the team of august clinical academics left the podium the tables and chairs were cleared and to our surprise a full band layout was installed, including amps, speakers, drum-kit and microphone stands. The time was 12pm so I assumed the stage was to be used for a student activity of some type.

I was wrong and I was right. Isaac and I were now invited to take front row seats among the students and informed that the ISTCRE’s own Rock band was about to perform a special concert in our honour. Imagine our surprise when the bass guitarist and co-leader stepped out with a bunch of seven students… only to be revealed as Rector, Javier Sotomayer.

There followed a joyous half-hour jamming session which concluded with their signature tune, the Scorpions ‘Wind of Change’. And they were good. Really, really good. But we weren’t allowed to sit down. Instead a group of cheerful and attractive young students dragged me and Isaac up from our seats and got us dancing. If only BBC’s Question Time ended the same way every week I’m sure its ratings would rise astronomically!

Lunch followed and then another very positive editorial meeting with the journal’s Board. Every part of the day was exciting and memorable and Isaac and I both came away impressed and uplifted by the special relationship which clearly exists between the ISTCRE’s teaching staff and its students.

A Bright Future Ahead Thanks to Dedication, Passion and Hard Work

ISTCRE trains over 2,000 paramedic students a year from its two campuses. As well as providing paramedics for Ecuador it also trains paramedics for around 9 other South and Central American countries, including neighbouring Peru, Colombia, Brazil and Honduras—all under the auspices of Cruz Roja.

Its passionate commitment to improving evidence-based clinical education across South America is undoubted since, as well as establishing CREMYAP and its own already highly-respected clinical research journal, its next ambitious project is to establish South America’s first paramedic university—a project which is enthusiastically supported by Cruz Roja Ecuatoriana and the wider global Red Cross community.

While in Quito I gained a crucial insight into the amazing and dedicated work that Cruz Roja Ecuatoriana is doing to care for the people of Ecuador and also for many of its neighbouring countries. Not only does it provide ambulance care but it also responds to natural disasters, rescuing victims and treating entire communities who have been displaced—most recently after the 2016 earthquake which devastated the country.

It also offers support to migrants entering Ecuador from neighbouring countries, and, as we reported on in our last edition, one of the most vital things it does in this area is reuniting families who have lost contact with each other. On top of this it trains Ecuador’s military in medical and general healthcare so they can respond better to disasters and also provide a better level of support to the population day-to-day.

It also plays a vital role in healthcare education and, at a time when AIDS and HIV are on the rise across South America, simply teaching people about the risks and how to avoid harm is a vital but very challenging undertaking.

Add onto this the work it does inoculating children and providing a working blood transfusion service nationally and you begin to get an understanding of what a vital role the National Red Cross in Ecuador plays in the life and well- being of its all-too often hard-pressed population.

Since our visit the charismatic and inspirational founder of ISTCRE and CREMYAP, Javier Sotomayor, has departed from his role of Rector.

But the beating heart of Cruz Roja Ecuatoriana is most certainly ISTCRE and CREMYAP. They are the ones that are not only providing free ambulance care across this very proud nation but also bringing hope for the future by training more and more paramedics and doing more and more prehospital research so that the overall quality of ambulance care continues to rise.

However, his former deputy, Dr Victor Daniel Malquin Fueltata has taken up the role of Rector and, as well as ensuring much-needed stability to both organisations, he is determined to use his own impressive medical knowledge and leadership skills to carry on the blazing flame of innovation and improvement that his friend and predecessor lit for Ecuador back in 2004. Their next project is to form a much-needed university of paramedic science. I have every confidence they’ll deliver on this as well. So, in closing, I urge as many of Ambulance Today’s friends in the global ambulance family to please make contact with ISTCRE and CREMYAP and offer them any support that you possibly can.

Ambulance Today was started by Declan Heneghan on Sept. 11th 2001 and to this day our sole goal is to strive to support and promote EMS and the fine work undertaken by ambulance services across the globe at every opportunity. To keep up to date with the latest, most innovative and interesting prehospital emergency news, feel free to join one of our WhatsApp groups where you will recieve regular content and discussion with like-minded, passionate EMS professionals:

Quality content

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop UK

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Games Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Best Betting Sites

- Best UK Online Casinos

- New Horse Racing Betting Sites