From the Africa Desk of Ambulance Today: A Case Presentation of Electrical Alternans in the Field

https://chat.whatsapp.com/AfricaDeskFeedback

Published in Ambulance Today, Issue 1, Volume 16, Around the World in 80 Questions, Global Clinical EMS Special, Autumn 2019

For this Africa quarterly, I will be discussing a cardiac patient encountered on a remote site in Africa and the unique challenges faced by the paramedic and his support team.

Patient Presentation: A patient presents at a remote site in the Southern DRC around 07:15 on a Saturday morning, with the patient’s chief complaint being shortness of breath (SOB) and swollen legs. The patient is brought into the emergency room and the consultation process commences. On first examination the findings are as follows:

Observations/Vital Signs on Initial Assessment

- Heart Rate: 108 – Regular

- Blood Pressure: 158/91

- Temperature: 36.8

- Pupils: PEARL

- Oxygen Saturation: 75% on an FiO2 of room air

- Respiratory Rate: 32 bpm

- Respiratory Effort: Rapid and labored

- Skin Colour & Appearance: Flushed and warm

- Blood Sugar: 7.1 mmol/li

- Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test: TDR –

Physical Examination

- Head & Neck: NAD

- Chest: Cardiac Auscultation detects Miåtral Regurgitation – Lungs clear Abdomen Distend, Pitted Oedema on all Quads – No Ascites

- Pelvis: NAD

- Upper Limbs: Oedema in fingers and wrists – no pitting

- Lower Limbs: Pitted Oedema up to the knees

- Back: NAD

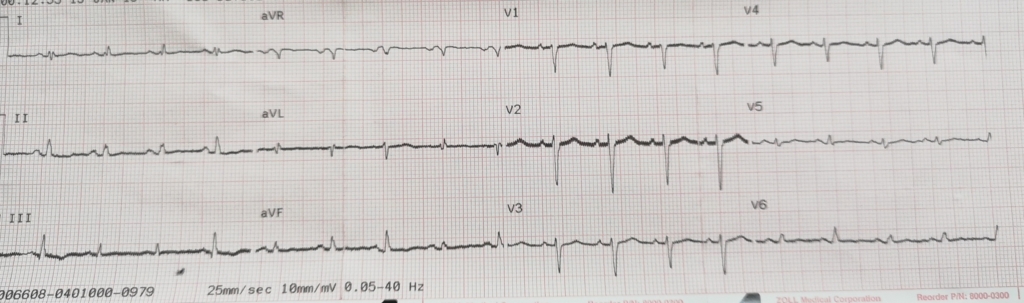

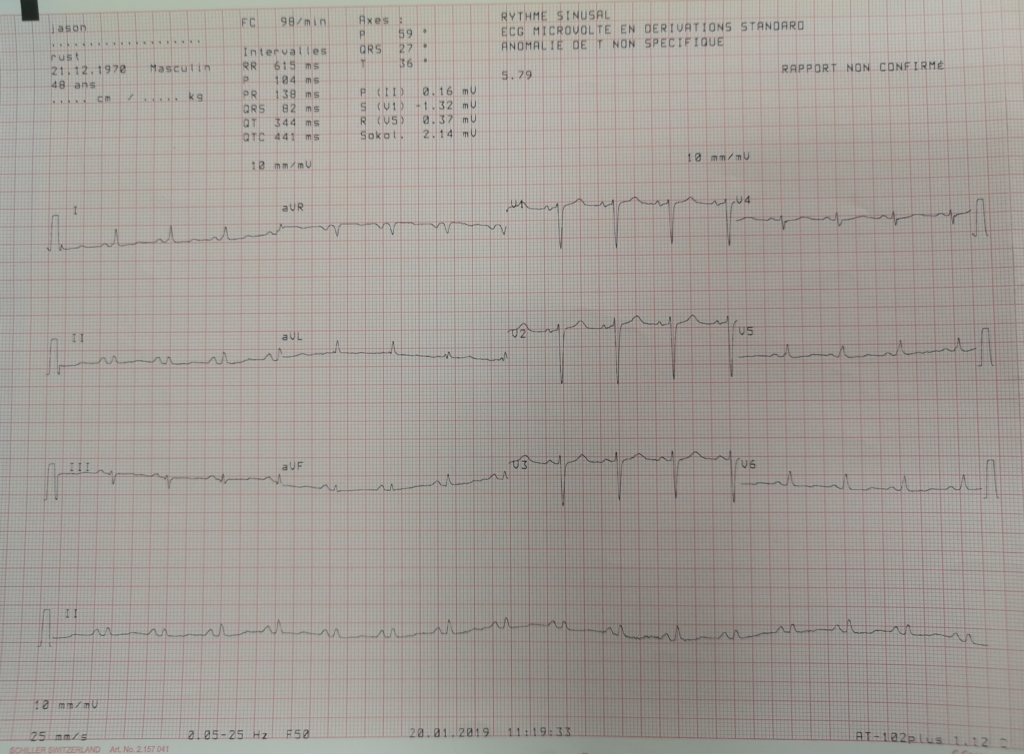

- ECG – 12 lead: Electrical alternans and Atrial hypertrophy

- Other: Pulsus Paradoxus noted in both radial pulses

Preliminary Diagnosis

- Date/Time: Acute Pericardial Effusion

- Date/Time: Differential Diagnosis of Mitral Regurgitation

The ECG findings of electrical alternans are usually associated with pericardial effusion (with the potential to lead to pericardial tamponade) and is due to the periodic wobbling of the heart in the pericardium. The significance of the pulsus paradoxus adds strength to this initial diagnosis. Without access to an ultrasound or X-ray, a definitive diagnosis could not be made and based upon the entire patient presentation, including excessive weight, short neck and history of two malaria positive tests over the past 7 months, a decision is made to evacuate the patient off-site to a cardiac ICU unit in Johannesburg, South Africa. In further consultation with the top cover support Dr, palliative care, maintaining oxygen saturation by means of supplemental oxygen (done via nasal prongs at 3 to 4li/min to maintain Sat’s of 90 to 93%) and the insertion of a TKVO IV line is agreed upon.

If this patient was in an urban setting or even a rural setting with rapid access to a Cardiac ICU, a definitive diagnosis and ACLS treatment could be initiated forthwith in a controlled multi-team clinical setting.

The Challenges Faced by the Team

Plans are put in place to begin evacuating the patient, the nearest landing strip only has daylight landing rating, so the patient would need to be there before 16:00 to facilitate the fixed wing evacuation. Before this can happen, multiple processes need to be initiated: approval gained from the insurers, an evacuation company needs to be appointed to do the flight, landing clearances must be granted by the DRC aviation authorities and the patient needs to be taken there by road—a 2-hour road trip in a 4X4 ambulance on a muddy, wet and potholed gravel road. In this instance, for a variety of reasons, landing clearances are taking longer than usual so a decision is made to charter a light aircraft—the Cessna Caravan (non-pressurised)—and to move the patient from the landing strip to the nearest largest town with night landing capability (so clearances can be obtained for that evening and because it has a good hospital nearby where the paramedic can keep the patient stable).

It must be noted that once the paramedic leaves the work site, he is working alone with the patient, with only the equipment he chooses to take for the road transfer, the chartered flight and the hospital stay. They eventually arrive at the neighbouring large city in the DRC and move the patient from the airport to the nominated holding hospital, where the paramedic settles the patient in—managing, monitoring, and continuing to co-ordinate the evacuation with various flight and insurance desks. Due to ongoing political instability in the region, the airport with night landing capability is shut down for the evening and the paramedic must sit it out until sunrise with his patient.

At sunrise the whole process starts all over again, to get clearances and wait for the fixed wing ICU jet from South Africa.

The Patient on (Ongoing) Re-Examination

Throughout the night the paramedic kept watch, monitoring and keeping the patient attached to the various monitors he dragged with him from the work site. Upon early morning re-examination a few new flags have popped up: abdominal cellulitis, a raised fever (37.8 C) and a positive malaria test result. They are also able to do a chest X-ray and notice a widened mediastinum and the presence of early pulmonary oedema developing in the base of the lungs. A third 12 lead ECG is done to see if there is developing ischemia or signs of an infarct – none are present. The fever is managed with IV parfalgan (paracetamol) while oral antibiotics and coartem are started for the infection and malaria. The paramedic discusses the ongoing care with his top cover Dr life line, and a Dr in the hospital. The diagnosis does now appear to be definitive – that of pericardial effusion.

The Flight Evacuation

Finally landing clearances are obtained (which is another story in itself) and a landing ETA is finalised, for around 17:00 on the Sunday afternoon. The patient is loaded into an ambulance with the paramedic and all his medical gear and is moved to the airport. As the plane is on final approach, the heavens open and it starts raining. After a detailed, comprehensive and wet handover, the patient is loaded onto the jet and they depart for the awaiting Cardiac ICU team in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Case Close Out

34 hours have now elapsed since the patient was initially seen by the paramedic back at the work site. Throughout this time the medic has been by his patient’s side, giving comfort, reassurance and medical care as needed. Finally, sleep is possible but getting out of the wet and dirty work clothes, followed by a hot shower and a decent meal, must happen.

The patient arrived in Johannesburg and was admitted into care at around 23:00 on the Sunday evening – almost 40 hours since the original provisional diagnosis was made. Treating and moving the sick and injured in Africa presents one with unique challenges not normally encountered in the developed world, or discussed at most cardiac symposiums. Welcome to the life of the remote and austere paramedic in Africa.

Tell Michael what you think about this article through WhatsApp via the following link:

https://chat.whatsapp.com/Africa Desk Feedback

Equally, if you have any news items you would like us to run either in our magazine or digitally then please email the editor via: [email protected]

Quality content

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop UK

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Games Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Best Betting Sites

- Best UK Online Casinos

- New Horse Racing Betting Sites

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!